Review of Ken Burns Vietnam War +national Review

Give Peace a Chance

Requite Peace a Chance

In their new documentary series The Vietnam War, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick offer a sharp indictment of an atrocious war. Simply when it comes to portraying the antiwar movement, they lapse into troubling stereotypes.

This is a preview of our Fall issue, out October 2. To get your copy, subscribe.

Say what you will about the Vietnam War, it had a great soundtrack. Feature and documentary filmmakers take, of grade, long appreciated this—cue "The End" by the Doors for the unforgettable opening sequence of 1979'due south Apocalypse Now, and, about a decade later, Bob Dylan'south "A Difficult Pelting's A-Gonna Fall" for a long, wet, and ominous combat patrol sequence in HBO'southward documentary, Dearest America: Messages Home from Vietnam (1987).

The 1960s bred a generation of musicians with an ear for prophetic gloom, their songs seeming all the more inspired every bit a backdrop to the unfolding horror in Vietnam. Even a whimsical ditty like the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Bout" took on new and unintentionally sinister meaning ("The magical mystery tour is dying to take yous away / Dying to have you lot away, take yous today") when played over Armed forces Radio in Saigon in 1967, as reporter Michael Herr reminds us in his ain dark masterpiece about the war, Dispatches (1977).

Ken Burns'south twenty-ninth historical documentary, The Vietnam War (2017), co-directed with longtime associate Lynn Novick, falls inside this tradition of depicting the war. Burns'southward work—twenty-viii documentaries since his debut with Brooklyn Bridge in 1981—is usually known for celebrating America's iconic things (the bridge), pastimes (baseball game), places (national parks), and people (Lewis and Clark). He has, of course, tackled wars before—The Civil War series (1990), which made his reputation, and a 2nd Earth State of war series in 2007 (The War). Simply those are at least considered nationally redemptive wars—for all the death and sacrifice and less-than-perfect worlds that followed when the guns fell silent, the union was preserved, slavery was ended, fascism was defeated, and all under the leadership of men who have since been celebrated as national heroes—Lincoln, Roosevelt, Eisenhower.

If Burns tends to gravitate toward lighter topics, the Vietnam State of war is decidedly not one of them. So it was with some trepidation that I sat down to binge-watch the eighteen hours of The Vietnam War. Despite an occasional and, to my ears, strained suggestion that the war was in some ways the production of good intentions gone awry, this series is Burns at his bleakest. Unfortunately, this perspective is applied somewhat indiscriminately, to include antiwar protesters as well as policymakers.

Ken Burns's signature aural and visual style is on display in The Vietnam War—melancholy background music plunked out past what sounds like a lonely musician on pianoforte or a stringed musical instrument, the ho-hum visual panning and zooming of nonetheless photographs to advise reflection or regret, talking heads who render enough times and converse at sufficient length that viewers come to trust them equally knowledgeable interpreters of the by. Information technology's predictable and piece of cake to mock (simply search for "Ken Burns parody" on YouTube), simply, as in his earlier piece of work, this narrative style, tics and all, generally helps make a complicated story accessible to a wider audience.

Burns and Novick assemble some 80 "witnesses" (as they're called in the serial' promotional cloth), including veterans from both sides of the conflict, Vietnamese and American, whose collective and private voices are the film's greatest forcefulness. Researchers accept scoured the athenaeum for arresting footage, especially of gainsay, allowing the filmmakers the opportunity to stage visually dramatic and graphic set pieces for such critical battles equally Ap Bac, Ia Drang, Khe Sanh, and, of course, Tet. And the film features a soundtrack that in permission rights alone must have cost PBS the equivalent of the purchase price of a adept used B-52: Dylan'south "Hard Rain," Buffalo Springfield'due south "For What It'due south Worth," Jimmy Hendrix's "Are You Experienced," Simon & Garfunkel's "The Audio of Silence," and the Beatles' "Revolution," to name but a few. The Rolling Stones' "Paint It Black" is heard several times over multiple episodes in the series' first half, most tellingly when the song runs through the closing credits for the episode that takes us to the eve of the Tet Offensive. Something bad—something really bad—the song signals, is nigh to happen. Of all the songs heard on the soundtrack, for me "Paint It Blackness" best captures the filmmakers' accept on the war equally a whole—powered by a growing sense of dread as events take place and decisions are made that nosotros know are not going to plough out well.

With the exception of the 2012 film Burns made with his daughter and son-in-law about the Central Park V, The Vietnam War is his first documentary treatment of events taking place largely in his ain lifetime. Burns was born in 1953 and raised in Ann Arbor in the 1960s and early '70s, his father on the kinesthesia of the University of Michigan, so it would be surprising if he didn't take powerful memories of the Vietnam era (less true, I imagine, of his collaborator Novick, who was born a decade after). Though he was at the younger stop of the baby boom—also young to exist personally threatened past the draft—he grew upward in 1 of the campus epicenters of the counterculture and antiwar protests, an feel that has surely influenced his perception of the state of war.

The release of The Vietnam War in September will doubtless shape popular retentiveness of the conflict for years to come. The practiced news is that Vietnam War "revisionists"—those who argue that the war was a necessary, honorable, and winnable proposition until the liberal media confused the public and liberal politicians prematurely pulled the plug on farther armed forces assist to the Southward Vietnamese government—volition find little to sustain their viewpoint here.

In their interpretation of the war'south origins and conduct, the filmmakers accept relied heavily on reporter Neil Sheehan's Pulitzer Prize–winning 1988 business relationship A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Vann and America in Vietnam. Sheehan'south book was partially a biography of Vann, a prominent American military adviser in Vietnam when Sheehan covered the war in the 1960s as a immature wire-service contributor. And, brilliantly, through the medium of Vann'south life, Sheehan retells the history of the war from the 1940s upwardly to Vann'southward death in Vietnam in a helicopter crash in 1972. Of Vann, Sheehan wrote, "He saw much that was wrong nearly the state of war in Vietnam, but he could never bring himself to conclude that the war itself was wrong and unwinnable."

Most of the witnesses in The Vietnam War, including Sheehan himself, exercise not share Vann'south blindspot on that question. The overwhelming impression given through their testimony is that the anti-communist South Vietnamese authorities was a corrupt, ramshackle travesty, dependent on U.S. patronage from its founding in 1954 to its collapse in 1975, without political legitimacy. Through the testimony of their witnesses, Burns and Novick portray the Vietnamese Communist Party, the determined opponent of the sham Saigon government, every bit barbarous and ruthless, but propose nevertheless that information technology represented a powerful and genuine wave of nationalist sentiment. They practice not celebrate the eventual triumph of the Communists, only they arrive clear that this upshot was all but inevitable. The United states of america professed to exist fighting in defense force of a heroic independent ally, but instead stood in the path of Vietnamese self-decision. And in doing so, conducted a state of war that proved an awful waste of human life, both American and Vietnamese.

The bad news is that in their portrayal of the war'due south opponents, Burns and Novick are, at best, inconsistent, at worst, intellectually lazy.

The narrator (the excellent Peter Coyote, formerly of the San Francisco Mime Troupe), says in the serial' final episode, "Meaning tin can be found in the private stories of those who lived through [the state of war]." That is and has always been Burns'southward credo every bit a documentary-maker. He is not primarily an idea guy—he'southward a story-teller (which, of course, is key to his popularity). Story-tellers are necessarily selective—the stories they choose and the ways in which they make up one's mind to tell them determine the narrative's larger purpose.

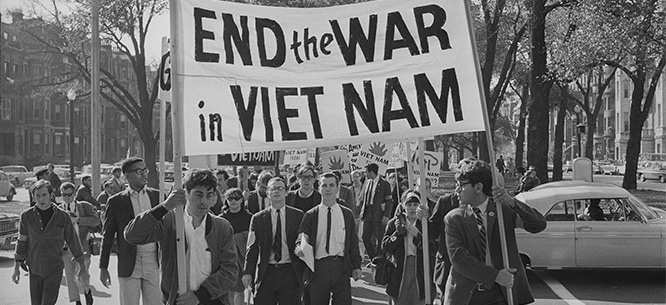

In the stories they tell in the series, Burns and Novick manage simultaneously to offer a thorough indictment of the state of war, and a dismissal of most of the people who were committed to catastrophe it. Information technology'south both antiwar and anti–antiwar motion. The 1 protest against the war the film truly admires is the October 1969 "Moratorium," which turned out several million people in peaceful protest across the state, and was indeed an impressive achievement on the role of organizers and participants. Merely in the series, it is used to denigrate the residuum of the movement. "It's nice," ane participant declares, "to go to a demonstration and not have to swear allegiance to Chairman Mao." Far also often in the trademark Burns panning and zooming shots of still photos of those other protests, the focus comes to linger on Viet Cong flags or Communist Party banners or the similar. This is a part of the story, to be sure—but simply a role. It leaves the viewer with the impression that hundreds of thousands of Americans, gathering in New York, Washington, or San Francisco, were indeed swearing allegiance to Chairman Mao, Uncle Ho, or Comrade Brezhnev—rather than, say, exercising the rights and responsibilities of citizens to claiming a war that they regarded as inconsistent with American interests and values.

In their treatment of antiwar protestation, Burns and Novick divide their witnesses and their stories into two groups: one honorable, the other doubtable. There are, firstly, those who turned against the war because of their own experiences: veterans, such every bit the novelist Tim O'Brien, and the poet W.D. Ehrhart, amid others; Ballad Crocker, the sister of a Chiliad.I. killed in action; Eva Jefferson, the daughter of another G.I. who fought and survived. We larn, through the interviews, a lot about each of them, as individuals also as historical actors. Their stories are presented in a way that gives them depth, legitimacy, and honor. They learned something almost the war the hard way, and viewers can—and should—sympathize with them.

What about the protesters who were not veterans, or didn't know or lose someone serving in the war? They stood side by side with antiwar veterans, and, one might think, deserve equal consideration and honor. Instead they are treated sparingly and shabbily. I can only call back two such individuals: a man and a adult female who had been students at that time. (I don't mention their names considering it's non my intent to criticize them; the choice of what to present was non theirs, just that of the filmmakers.) Both witnesses in this category substantially remain ciphers. Unlike, say, Tim O'Brien or Ballad Crocker, they don't have a back story (in fact, we're not even told that the female protester attended Barnard—I just know that because she happens to be a friend of a friend). In their limited screen time (the Barnard woman appears only twice, and in neither case for long), they are presented to united states not through their individual stories, but rather every bit abstruse representatives of the genus "protester." They may not be portrayed as bad people, but neither do they come up beyond equally peculiarly sympathetic.

Nigh strikingly, both of them, in private concluding appearances in the serial, wind up apologizing for their deportment in the antiwar move. Later the male protester returned from the "Mayday Tribe" protests in Washington, D.C. in May 1971, which involved disruptive ceremonious disobedience (although not, as the film implies, widespread violence), he concludes, "our whole strategy was wrong." And the female protester, in her 2d and terminal appearance in the last episode of the series, apologizes for calling returning veterans "infant-killers," and says that it still grieves her to recall doing that. "I'one thousand lamentable," are her final words—the final words we hear from any antiwar protester. So, out of a full of 80 witnesses who appear in The Vietnam State of war, a grand total of two fit the common stereotype of the Vietnam protester—students with no direct experience of or connexion to the war—and they're both presented as existence sorry for what they did. Were there truly no unrepentant protesters for Burns and Novick to interview?

From the mid-1960s on, many antiwar protesters actually regarded Vietnam veterans equally potential allies in opposing the war—defying the stereotype of New Leftists spitting on returning soldiers. Hither, released P.O.West. Lt. Col. Robert 50. Stirm is greeted past his family, Travis Air Force Base, March 17, 1973. Courtesy of AP Photo/Sal Veder.

One other annotation on "baby-killers." Karl Marlantes, a Yale-educated Rhodes Scholar, went to Vietnam as a junior officer in the Marine Corps, where he won a Navy Cross for leading an attack on a North Vietnamese bunker. He would later write a best-selling novel based on his wartime experiences. In his own plough as a witness, he deservedly gets the Ken Burns treatment, and comes beyond on screen, as I have no doubtfulness he is in person, as thoughtful, articulate, and principled. When he returned to the Usa from his tour of duty, he tells Burns and Novick, he had a dismaying experience on arrival at Travis Air Force Base in California. His brother, he says, picked him upwards, and told him to prepare to run a gauntlet of angry antiwar protesters gathered exterior the base. Before he fabricated it into his brother's auto, he was called a baby-killer, or the equivalent, and antiwar protesters pounded on the auto as it pulled away.

Grandaybe it happened equally remembered and described. Three meg Americans served in the military machine in Vietnam, and perhaps twice every bit many took part in antiwar protests at dwelling house. In a time of loftier political passion, at that place must have been some uncomfortable personal confrontations—as in the Barnard woman's remembrance. Perhaps Ken Burns, growing up in Ann Arbor, witnessed something similar. Merely how representative is that memory? Information technology certainly doesn't accordance with my own. In a decade of antiwar activism, I never chosen a veteran a infant-killer (and would never have dreamed of doing then), never knew another protester who called a veteran a baby-killer, never fifty-fifty heard of anyone calling a veteran a baby-killer. (Fractional exception—the Weatherman faction of SDS, who in 1969 decided to demonstrate their revolutionary credentials by labeling G.I.southward "pigs"—which only reinforced their pariah status in the antiwar community.)

Memory is unreliable, which is why historians prefer documents—similar the actual television receiver footage that Burns and Novick utilize to illustrate their story about what awaited returning veterans at Travis. It does non show protesters engaged in fierce or confrontational activities. What it shows is a group of antiwar protesters continuing peacefully on the sidewalk outside of an airport with placards and leaflets. The prototype is at odds with the narrative. I of the protesters is wearing a T-shirt that clearly reads "Agile Duty G.I.s Confronting the War." From the mid-1960s on, antiwar protesters like this group, and similar myself, regarded returning Vietnam veterans as potential allies, and the movement equally a whole increasingly made efforts to reach out to them. That's what is happening in this particular footage. Unlike their treatment of the state of war, which draws heavily on the historical record, similar the Pentagon Papers, as well every bit personal memory, Burns and Novick prefer anecdotes in their label of the antiwar movement. But the record is out there, if they had simply gone looking for it. News of G.I. and veteran protests filled antiwar publications. A network of antiwar G.I. java houses, supported by the noncombatant antiwar movement, grew up effectually military bases. Past 1971 Vietnam Veterans Against the War was the cutting edge of the antiwar movement—and also the virtually vocal in publicizing and condemning American atrocities, including the killing of civilians, in the war.

The baby-killer taunt is a good example of a "zombie prevarication" (a prevarication that won't die no matter how many times it's refuted), and the worst thing I tin can say almost the Burns and Novick series is that it practically guarantees this particular zombie volition remain undead. It goes paw-in-hand with another myth that Burns and Novick might have subjected to critical investigation and aid dispel, merely chose not to. As Holy Cross sociologist Jerry Lembcke, himself a Vietnam veteran, shows in his 1998 book The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam, there is no contemporary show (newspaper, magazine, or television set news accounts) of antiwar protesters ever spitting on a returning veteran. It was only fifteen or twenty years later on, following the release of the Rambo movies (sample dialogue: "Then I come dorsum to the globe [from Vietnam] and I see all those maggots at the airdrome . . . Spitting. Calling me baby-killer . . .") that the notion that antiwar protesters spent long hours lurking effectually air bases hoping to harass and dishonor returning veterans took off in right-wing lore. Lembcke is still around, however writing about the handling of veterans on their return from Vietnam. Why wasn't he invited to exist a witness in the series?

To be off-white, Burns and Novick had a complicated history to recount; they would need at least another eighteen hours to do justice to every story worth telling near the Vietnam War (and even that might not exist plenty). Simply they made choices most the story they wanted to tell. They chose to paint the antiwar movement of the 1960s and 1970s in an unflattering lite, when in fact this movement, veterans and not-veterans alike, was the only truly redemptive story to come out of the Vietnam War.

Maurice Isserman teaches history at Hamilton Higher. He is co-writer, with Michael Kazin, of America Divided: The Ceremonious State of war of the 1960s (Oxford University Press, 1999).

This is a preview of our Fall issue, out Oct ii. To become your copy, subscribe.

clogstoundensicke.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/ken-burns-lynn-novick-vietnam-war-review

0 Response to "Review of Ken Burns Vietnam War +national Review"

Post a Comment